Who's the real MVP? Regular Season Adjusted Quarterback Efficiency (AQE) Results

Lamar Jackson isn't the most valuable player by this measure, and you can make the strongest cases for Brock Purdy or Dak Prescott

Check out the first the first installment of the Luck-Adjusted Efficiency numbers (free post) to get more details on the methodology below. I also have lots of information in past posts on Adjusted Quarterback Efficiency (AQE):

2023 SCHEME/LUCK-ADJUSTED RESULTS

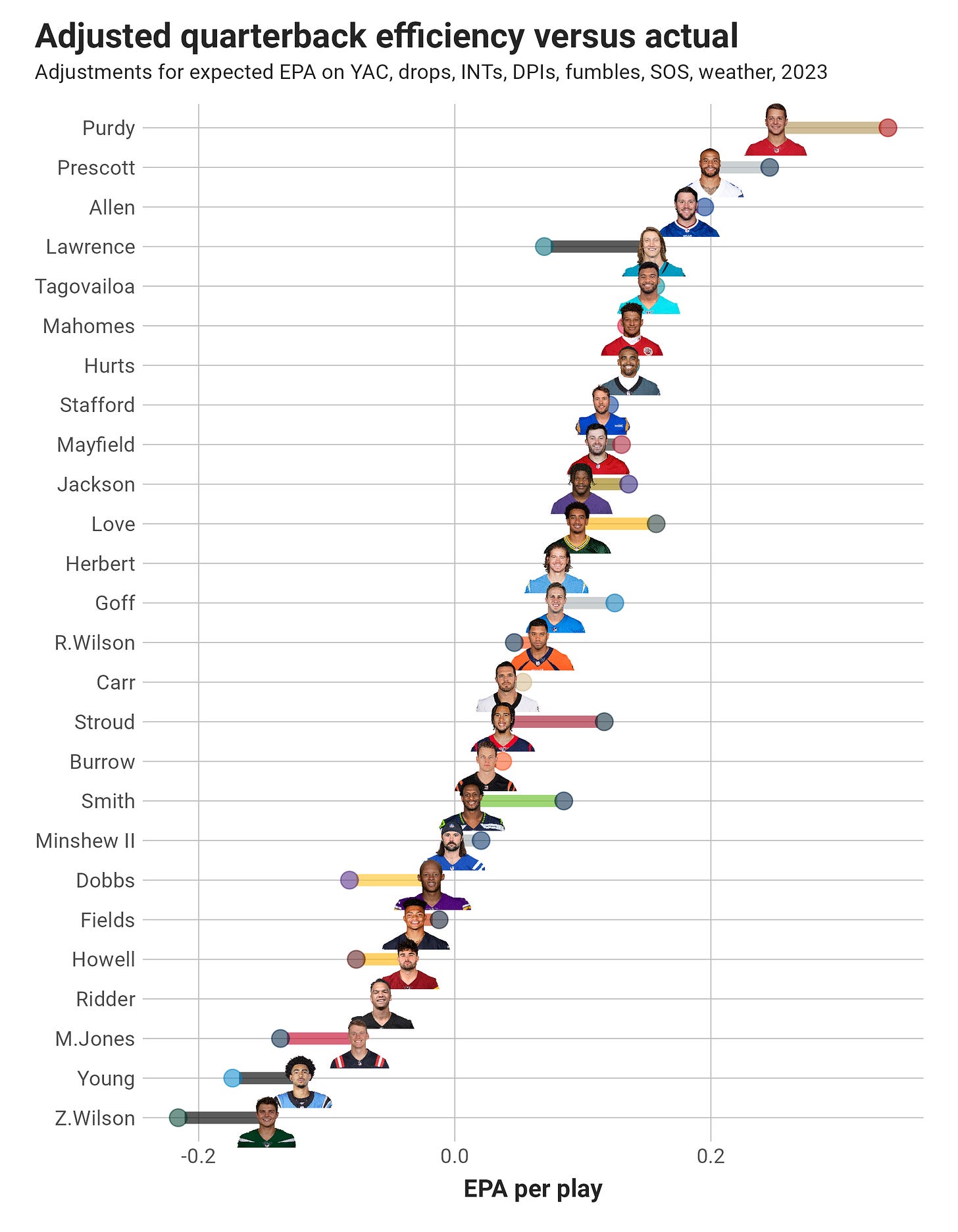

The plot below shows each quarterback who has 400 play involvements this season (dropbacks and designed runs), minus a handful who have been injured for the season and not played recently. There are two points for each quarterback: 1) The team-colored dot for the actual EPA per play the quarterback has this season and 2) The quarterback headshot representing the adjusted quarterback efficiency (EPA/play). There is also a team-colored line linking the two on each row.

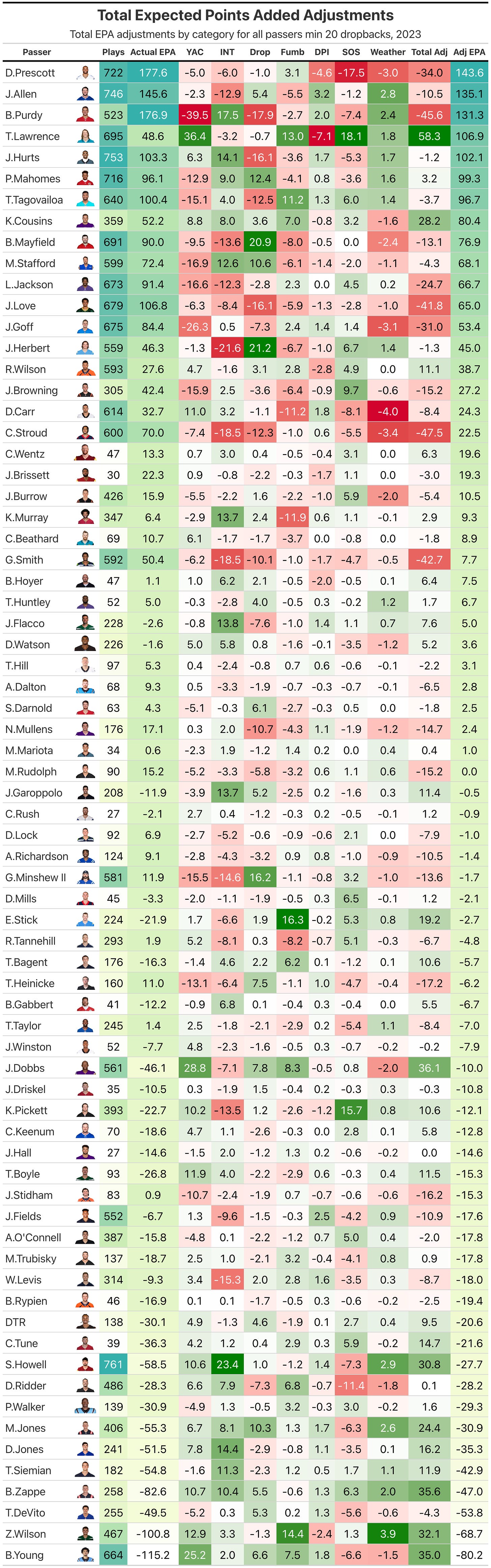

I raised the play-involvement cutoff to 400 for the final regular-season version to highlight those who played basically a season’s worth of action. It’s interesting to see where quarterbacks with 200-400 dropbacks like Kirk Cousins or Jake Browning land versus the others on this list. But it also gives poor optics for comparison, in my opinion. Would Cousins or Browning have finished an entire regular season at second (yes, second) and 13th, respectively, in adjusted EPA per play as they did in their limited action? My guess is “very likely not”, so I didn’t include them to confuse the results with varying sample sizes. They are part of the total adjusted EPA table below, along with all quarterbacks with all 72 quarterbacks with at least 20 dropbacks this year.

Let’s address the elephant in the room with Lamar Jackson ranking 10th in adjusted EPA per play and total adjusted EPA (excluding Cousins). Barring Cowboys, 49ers or Bills fans ballot stuffing, Jackson will be the NFL MVP. So why the disconnect? The cases for and against Jackson each have their own explanations for why the advanced stats don’t match up with public perception. In the case of Jackson defenders, it’s that the numbers are missing the impact that Jackson brings outside of the plays included (mostly non-quarterback rushes), and that he’s overcoming lesser surroundings, therefore responsible for a higher degree of the offensive success than other quarterbacks. For Jackson detractors, it’s simply confusing team success and quarterback wins with individual quarterback value. I’m going to dig through both theories and try and figure out which is more credible.

Starting with pro-Jackson argument, I looked at his effect on rushing non-quarterback rushing success, and there’s definitely something to it. Previous research by Eric Eager showed that quarterback rushing frequency is an important variable for explaining non-quarterback rushing success. I’d argue the thesis that Jackson adds value to the Ravens offense in plays not included in his individual EPA stats is unquestionably true. The real work though is figuring out the matter of degree, and whether or not that missing value can close the gap with other quarterbacks with significantly higher EPA numbers. In Eager’s work, the quarterback effect was significant, but also ranked sixth most important among the variables he tested, lower than the PFF play-level grades for run blocking and ball-carrier rushing. The Ravens ranked eighth in PFF team rush blocking grade in 2023, and their non-quarterback rushers had a weighted grade in the top-10. Those grades don’t explain how the Ravens ended up second in rushing EPA per play during the season, but they give us part of the explanation.

Bridging the gap means giving Jackson the rest of the credit, which would equal somewhere from 0.02-0.04 EPA per non-quarterback rush, which matches up nicely with the splits I found for Ravens rushing efficiency when Jackson has been on/off the field during his career. If we multiply that across the 326 Ravens non-quarterback carries this season with Jackson on the field, we can estimate Jackson’s value add at around 5-15 expected points. If you give Jackson credit for the full 15 expected points, that would raise his total adjusted EPA to 8th most, not near the category of the top producers. If you go further and say that quarterback don’t get full responsibility for their passing/rushing EPA, and do something like cut everyone’s total in half before adding the 15 expected points for Jackson, it gets closer to closing the gap, but still leaves Jackson more than 35 expected points lower than someone like Dak Prescott, who did play an additional game. The problem with making this special adjustment for Jackson is that you’re not doing something methodologically similar for other quarterbacks. You’d presume that Josh Allen’s and Patrick Mahomes’ special abilities passing and running add something to their teams’ non-quarterback rushing efficiency too.

When assessing the rest Jackson’s supporting cast, it’s tough to make the argument he has anything beyond a marginal deficiency versus some of the other quarterbacks well above him in adjusted EPA. For receivers, Brock Purdy and Tua Tagovailoa appear to have great advantages, with their teams’ receiving grades ranking first (90.5) and second (87.1). The Ravens’ 13th ranked receiving grade isn’t much different from the Bills (11th), and marginally lower than the Cowboys (4th, 80.9 vs 75.2). For pass blocking, the Ravens have a better PFF grade (4th, 73.7) than the Bills (11th, 69.5), Cowboys (14th, 67.7) and 49ers (26th, 55.0). If you view receiving weapons as more important than pass blocking for quarterback efficiency (there’s good case for that), then Jackson would make up almost all of his adjusted efficiency gap with Tagovailoa, and a portion of that with Purdy. Yet there isn’t evidence that receiver and blocking adjustments would close much of the gap between Jackson and Allen or Prescott.

So how do Jackson skeptics explain why he’ll likely get nearly 100% of first-place MVP votes while trailing other quarterbacks so much in efficiency. First, the above portion on the pro-Jackson case applies somewhat, but more importantly it’s about what sticks out in our minds after screening for team success and living in a Red-Zone, highlight-saturated world. For team success, I think the best quantified explanation is that poor quarterback performances in team wins matter less, and the same thing for great quarterback performances in losses. We’ve all seen the narratives completely shift for teams and players based on how a couple plays affect games, often plays that aren’t even in the critiqued players’ control.

When I eliminated from quarterback EPA efficiency games when they had a lower than 50th percentile EPA per play and won, plus those with a higher than 50th percentile and lost, Jackson’s EPA per play benefited more than any other quarterback, and exactly matched that of Prescott and Allen. Jackson had eight games of below 50th percentile EPA per play, and the Ravens lost only three of them. The Ravens didn’t lose a single game when he had good efficiency. Prescott had three games of poor efficiency and the Cowboys lost all of them, while the Cowboys lost two more games in which Prescott had 82nd (first Eagles game) and 70th (Dolphins) percentile efficiencies. The mix of bad wins and good losses is more similar to Prescott than Jackson for Purdy and Allen.

The other factor is probably the impressive nature of Jackson’s highlights, which come several times during each game, and are featured heavily post-game for Ravens wins, even if his overall performances were lacking. My anecdotal perception from the first two thirds of the season was general acknowledgement that the Ravens offense was inconsistent, at best, but that impression didn’t weigh much on latter-season perceptions, as the Ravens were still able to emerge with a great team record. Most would probably also be surprised to see that Jackson’s negative adjustment to EPA in this analysis is significant, based on YAC over expectation and INT-luck. Jackson doesn’t have as big of a negative adjustment as we see for Purdy (mostly YAC and drop luck) or Prescott (mostly a weaker SOS), but it’s not as diametrically opposed as some perceive.

I don’t really have a big issue with Jackson being the MVP this year, as long as those voting for him are honest about what’s driving their perceptions. The focus on what’s missing from EPA, or his unique, unquantifiable abilities are obscuring the real drivers. If you’re motivated to think of Jackson as MVP because his poor performances didn’t hurt the Ravens in the W-L column, and his great games helped take down other great teams, then you can just acknowledge that. I tend to view the sequencing of poor/great performances as more variance than some sort of planned “playing up to the occasion.” If you don’t see it that way, and believe that the “winning moments” matter more than consistently valuable play, even in losses, you have to at least be honest about it.

As far as how I would vote, I’m torn between some of the top candidates. I think Prescott and Purdy have the strongest cases, with one the total adjusted EPA leader, shouldering a huge load for his team, and the other the clear efficiency King, even factoring in awesome surroundings. Based on confidence in who these quarterbacks are over the samples of their careers, I’d vote for Prescott first, Purdy second. I’d have Allen third, and have Jackson as high as fourth, but not above the others in terms of what he added to team value this year.

This is totally fascinating and as such an opportunity. I'm in the medical field and this reminds me that comparatively the US health industry is the most scientific in the world. We have metrics up the wazoo, more than any other country. And in all sorts of ways that's a good thing. a great thing. I'm happy to be a part of it, really. But at the same time no one would say that that translates into better health outcomes compared to a bunch of other countries. I do not want to get political at all here about why this is happening; just to note it and how similar on one level it is to this year's MVP vote.

Statistically Lamar should't be considered for the MVP vote, yes. That he will probably win it or even if he comes in second or third, just messes with the statistical models. But ultimately praxis always beats modeling no matter how good statistical modeling is perceived to be. By definition. The trick then is to figure out how to incorporate this year's vote or Cam's MVP win a few years ago into the statistical model so it better reflects reality. That's a difficult trick for sure. Lamar is a huge outlier but he's also pointing to future outcomes like this, occasional as they will be. How to anticipate this statistically is a challenge to put it mildly beginning with as to why this is happening by sorting through all the muddle-headed rationalizations out there.