Weekly Commentary & Review #13

How the new OT rules have fried pundit brains, why we shouldn't pump up Mahomes beyond reality, and it's okay that winners are luckier

I’m back to writing these weekly commentaries now that the season is over and I’ll have more time to digest the good, bad and ugly in football discourse out there. Don’t worry, this offseason you’re still going to get all of my free agency analysis, proprietary Improvement Index, the consensus mock drafts, combine breakdowns, pre-draft studies and post-draft analysis.

Please like and share this post if you’re so inclined and want to spread some rational thoughts to those drowning in a sea of takes.

TRULY THE DUMBEST DISCOURSE

The new playoff overtime rules have been a huge success to two regards, one intended, the other not:

Eliminating the decision advantage that previous swung heavily towards getting the ball first by denying both teams the chance to possess the ball

Opening up a seemingly endless cycle of overconfident takes that, unsurprisingly, happen to criticize the decision of the losing coach

We’re in a take-fueled crisis of biased thinking, but to quote John F. Kennedy on the Chinese character for crisis and its dual meaning: “In a crisis, be aware of the danger--but recognize the opportunity.” Let’s face it, if public perceptions and those of sports pundits were unbiased, I’d mostly be out of a job (or would I be the No. 1 football pundit?). As frustrating as it can be to see talking heads shout about how “shocked” they were by decisions they hadn't ever thought about before, it does provide a vacuum of opportunity for rational analysis to fill.

The first step is to separate our intuition and results bias from a diligent analysis of the decision. The losing team’s decision will be seen as wrong when the results are bad. At the very least, the results couldn’t have been worse if a different decision was made. If we assume a world of zero variance, the 49ers always lose when choosing to receive the overtime kickoff, but have some unknown chance of winning if they defer.

We have to look for the evidence outside of the one example we saw with our eyes, and most of the work on this was done two years ago when the new playoff overtime rule was proposed and approved. The two examples I can find of public analyses come from the NFL’s Head of Data and Analytics Michael Lopez and ESPN’s Brian Burke. For what it's worth, I view Lopez and Burke as two of the best thinkers and practitioners of football analytics, in the upper tier among others working in the field.

Lopez presented his findings on the new playoff overtime rule proposal to the NFL’s competition committee, and his ultimate finding was that the new rules gave the receiving team a 51% to 49% win probability advantage, with an explicit acknowledgement that the probability lean could flip in either direction when you adjust assumptions for offensive/defensive skill, weather/wind direction and end zones where it's easier to kick.

Burke’s simulations found that the receiving team won 50.2% of the time under the new rules, versus 53% under the previous rules, and 57% going back to the traditional, first-score-wins format (pre-2010 postseason, pre-2012 regular season). Burke acknowledges potential errors in assumptions, which could swing the simulation results in the other direction.

Another piece of public evidence to consider is an informal poll ESPN’s Seth Walder conducted among his extensive front office analytics contacts. This 10-person sample registered equal votes for receiving and kicking (plus a confidence skew towards kicking), with the plurality of votes for “almost 50-50”. Keep in mind that the poll was taken after the Super Bowl, and I doubt NFL analytics staffers are completely immune to results bias. A concrete example of results bias is a real-time poll conducted by Lopez that switched from 53% “receive” before the result to 61% preferring “kick” 24 hours later.

Relatively few are going to know about the simulations from Lopez and Burke, or the thoughts of NFL analytical staffers and will, instead, go by their results-biased intuition and what pundits are telling them. Further confusing things are examples of overconfident opinions with false statements (the evidence points strongly to Shanahan knowing the rules after discussing them with his analytics staff) among those who are, at least superficially, believers in evidence-based decision-making. Matthew Davidow, who has done quantitative work with in-game win probabilities, went as far as to call the decision “not close” in favoring kicking off first. Presumably Davidow has done some work on modeling this before making a declarative statement, even so, you can find previous examples of him making strong claims on decisions that were highly questionable.

I really don’t see how you can come away from the evidence with a stronger opinion than a low-confidence lean in either direction. This is where the dreaded “but full context is not in the model” comes into play, which certainly matters, but is more likely than not given too much weight confirming intuition. The Chiefs and their unstoppable offense is the context that renders models useless. You can’t give them four downs to score a touchdown on the second drive! I mean, theoretically you have four downs to score on the first drive too, but I digress.

The “Chiefs-offense” context is likely being misapplied in two ways:

Too high of a touchdown-rate assumption for the Chiefs if they can use all four downs

Too strong of an assumption that Andy Reid will always make the optimal fourth-down decisions for preventing a third possession

I conducted a “very scientific” Twitter poll, with buckets for the Chiefs touchdown probability using all four downs. It ended at 45% in the 50-75% bucket, 39% at 25-50%, 10% at 75-100% and 6% at 0-25%. The Chiefs drive touchdown-rate since 2018 is 30%, dropping to only 20% this year with offensive struggles.

PFF’s Timo Riske has done research on the effect of playing with all four downs on enhancing touchdown rates, and his conclusion is that a good offense like the Chiefs with ample time would score a touchdown on roughly 50% of drives. My Twitter poll skewed to the over 50% buckets, meaning the public perception - as measured by my sharper-than-average followers - is probably too high.

The Chiefs in overtime weren’t going to use four downs to score a touchdown no matter what, because their win probability doesn’t go to zero with kicking a field goal. Our assumed touchdown rate for the Chiefs in that situation should be somewhat lower than the 50% in a touchdown-or-die scenario. Inside of field goal range, there is some yards-to-go tipping point for Reid to kick rather than go-for-it. Many assume that the third-possession advantage for the receiving team doesn’t exist because the second possession team always knows what they need to do to win, and will always press all the way towards doing only that.

But let’s think about this in reality. Yes, the Chiefs went for it in overtime on fourth-and-inches on their own side of the field, a a fairly obvious go-for-it call during any time of the game, and one that I think generally conservative coaches like Reid and Shanahan would have called had it occurred during the first possession of overtime. But are we sure Reid would remain highly aggressive if a drive stalled out in field-goal range with a longer distance to go?

Three times in regulation the Chiefs kicked field goals on 4th & 6. For the average team, the conversion rate from that distance is a little under 40%. With Mahomes as a starter, the Chiefs have converted 3rd/4th down & 6 (included third downs to build a reasonable sample) 49% of the time. Is it that unlikely a conservative Reid will choose the chip-shot field goal and trust his high-performing defense? Going for the conversion is a coin-flip that automatically ends the game if you fail, and doesn’t necessarily seal the victory if you succeed.

If you play a different theoretical scenario game and assume the 49ers failed to score on their first drive, would Reid go-for-it out of field goal range on fourth down with 10-plus yards to go, as was the situation on two drives earlier in the game? It’s easy in many people’s heads to assume Mahomes & Co. are unstoppable with four downs, but the best estimates can’t say that. And while I agree you’ll get a better, more aggressive Reid during overtime than regulation, it won’t turn him into a go-for-it-at-all-cost advocate, as the perfectly optimal decision will sometimes be to play for a fourth possession.

MAHOMES DOESN’T NEED MYTHS TO BE A LEGEND

I gotta begin by saying something that’s obvious to anyone familiar with my work and opinions: Patrick Mahomes is the best quarterback in the NFL (it’s not close), and clearly on the trajectory to be the Great of All-Time™️. That said, following his third Super Bowl victory in the last five years, lots of what’s being written about Mahomes has veered off the rails of rationality and into hagiography.

Admittedly, I have an annoyingly contrarian tendency to point out how the consensus is going too far, even if they are, finally, headed in the right direction. In this case, the crowd fully capitulating to Mahomes being the clear QB1 is correct, but we still should try to present fair and unbiased evidence when making the case.

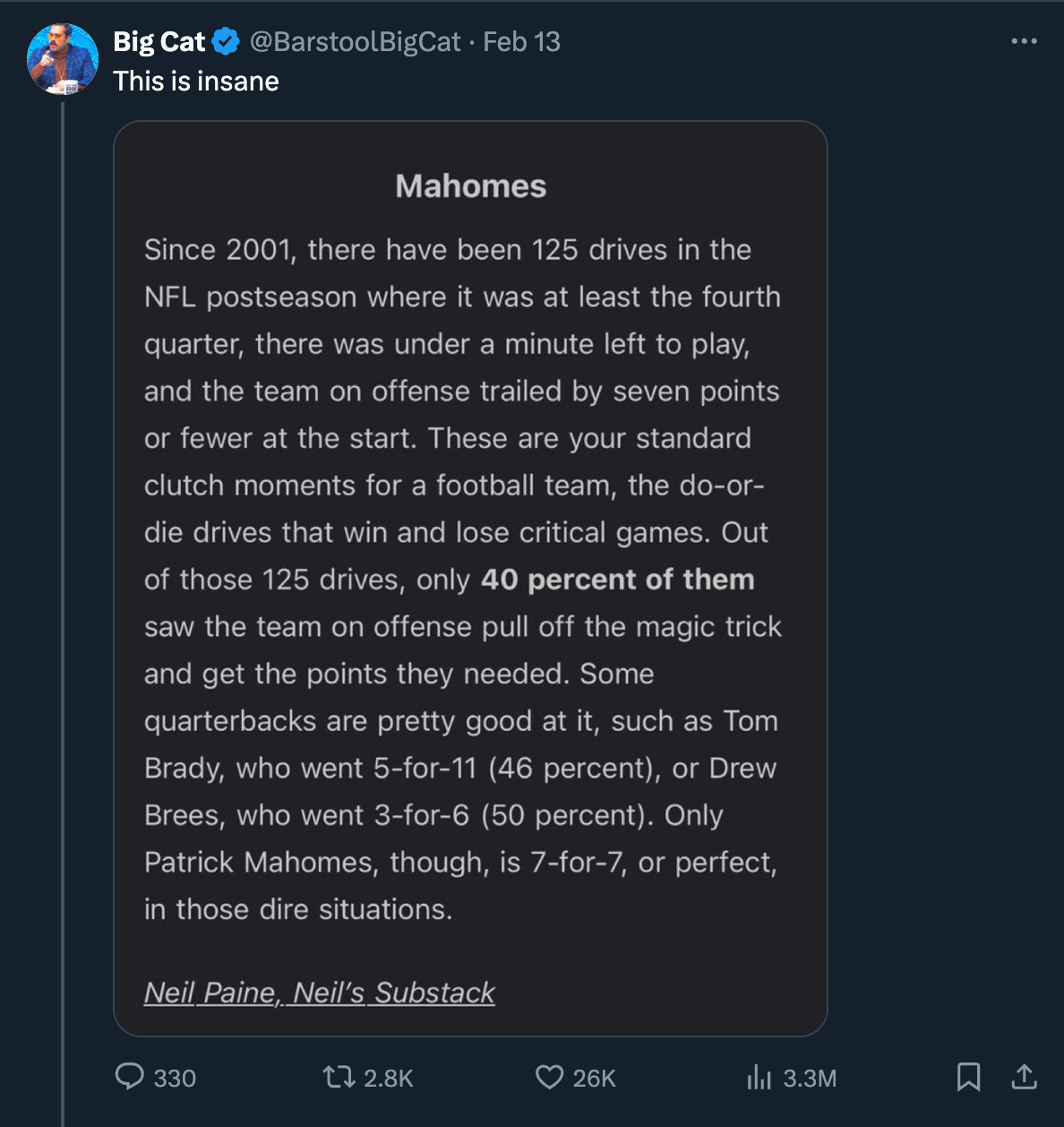

I couldn’t help but notice a blurb floating through social media from FiveThirtyEight writer and current substacker Neil Paine on the “impossibility” of stopping Mahomes. The biggest account I’ve seen share the blurb belongs to Barstool’s Dan Katz, and his post is currently sitting at 3.3 million impressions:

More details from Paine’s actual post on the parameters for this statistic:

It was the fourth quarter or overtime;

The drive ended with under a minute left to play;

And the offensive team was either tied or trailed by 7 points or fewer going into the drive.

Based on those filters, Paine found 125 drives in the postseason, with 50 (40%) resulting in a score to tie or win the game. According to Paine, Mahomes was a perfect 7-for-7 in those situations, versus 5-for-11 for Tom Brady and 3-for-6 for Drew Brees.

It’s an incredible stat, not just that Mahomes has been perfect when the crowd is worse than a coin-flip, but also because he’s so much better than other Hall-of-Fame quarterbacks. The problem is, the stat is not only a biased sample to provide the biggest “wow” effect, it’s straight-up wrong in its conclusion of Mahomes’ perfection.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Unexpected Points to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.