Targeting the right traits for successful tight end prospects

There's a smaller sample of elite, valuable tight ends in the NFL, but they share traits you can identify in college and combine metrics

Unexpected Points is a newsletter exploring the analytical side of the NFL. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

My tight end prospect analysis from a year ago was one of my more successful posts, in terms of interest and predictiveness. By focusing on a few athletic and production traits, you can identify nearly all of the successful tight end prospects to join the NFL in the last several seasons. Last year, the star of a deep class of traits was Sam LaPorta, the coverboy of the analysis.

The reason that I decided to focus on certain traits and not a more complex modeling process is simply the lack of sample. Small data set with only a handful of successes can easily lead to overfitting and poor of out-of-sample predictiveness. The best use of stats-based analysis for tight ends, in my humble opinion, is to carve and sort through the data to see what we can learn about the common traits of historically successful prospects, and apply those lessons to future draft classes. I’m going to look back at the historical evidence, and then apply the lessons learned to the 2024 tight end class, which includes a few strong contenders for elite outcomes.

Estimated draft position is overwhelmingly the biggest driver in other skill position models, but the correlation between draft slot and NFL success is smaller for tight ends. Travis Kelce and George Kittle, the top-2 tight ends in the NFL right now, were drafted in the 3rd and 5th rounds. Mark Andrews is the only other tight end to make an All-Pro team over the last four seasons, and he was taken in the back half of the 3rd round (two rounds after his team selected Hayden Hurst).

The elite tight ends of the last generation were more top heavy, with first-round picks Greg Olsen, Zach Ertz, Vernon Davis and injury-affected second rounder Rob Gronkowski. But even then, Hall-of-Famers Jason Witten and Antonio Gates weren’t taken in the first two rounds, and multiple All-Pro selection Jimmy Graham wasn’t either. This is my long-winded way of saying that we can’t simply plug in a draft slot and make minor adjustments to project tight ends like other positions. We have to dig to figure out what evaluators are missing or overvaluing on their recent early picks.

Part of the difficulty in tight end evaluation is a simple lack of reps to judge. George Kittle caught fewer than 45 total passes in his entire college career. In Travis Kelce’s breakout final college season, his 45 catches and 722 receiving yards ranked 159th and 102nd, respectively, among all FBS receivers. Now Kelce consistently ranks in the top-10 in NFL receiving yardage. College is simply a different game for tight ends, where coaches have built systems to work around the lack of pass-catching ability of an ever-rotating cast of blockers who can occasionally catch.

Tight end prospects are more uncertain projections than other skill position prospects who have roles more similar to what they’ll do at the next level. NFL evaluators will logically be fooled into falling in love with the tight end prospects lucky enough to fall into a coaching scheme that utilizes their talent, even if it’s lacking NFL upside. The level of confirmation and confidence you can derive from a limited exercise of watching prospect tape makes differentiating and rank ordering prospects extremely difficult.

With a laundry list of difficulties, how do we make progress evaluating and selecting tight ends? First, we can try to identify the broader traits that have led to NFL success, especially those that give all prospects a roughly equal standing to achieve. Second, we group together those prospects that are most likely to be successful by those traits, then be patient and wait until others act before jumping to take one from our list. Low confidence of rank ordering means lower priority to get the prospect at the top of the list, especially knowing highly productive tight ends are available late into Day 2 and beyond.

Drafting tight ends with the right mix of traits doesn’t guarantee each will be successful, but what we find is that you can narrow the pool to eliminate many who have almost no chance of success.

TIGHT ENDS MOSTLY WIN AFTER THE CATCH

Being able to stretch the seam and win down the field are important qualities for a tight end, and probably generate a lot of goodwill among tape evaluators, but they aren’t the primary way tight ends win in the NFL. If you look at the top-5 wide receivers in yards last season, none generated more than 35% of those yards after the catch.

Yet the top tight ends were YAC monsters, with Travis Kelce getting nearly half of his yards after the catch, George Kittle topping 50%, and T.J. Hockenson at 46%. Mark Andrews is a bit of an anomaly at only 30%, though yards-per-reception King Rob Gronkowski consistently averaged over 40% of his yards after the catch. Luckily, PFF has been charting what receivers do after the catch at the college level since 2014, and not only yards gained, but also tackles avoided, which could be even more important and stable.

I mentioned earlier how the lower volume for tight end usage at the college level leads to smaller sample, which exaggerates the variance for YAC numbers. Sometimes you break a tackle on the 30 yard-line and take it all the way for a score, sometimes the exact same play happens from the 10 and there’s only a third of the YAC to generate. Both plays had the consistency in the trait of a broken or avoided tackle, but the YAC numbers tell a drastically different story.

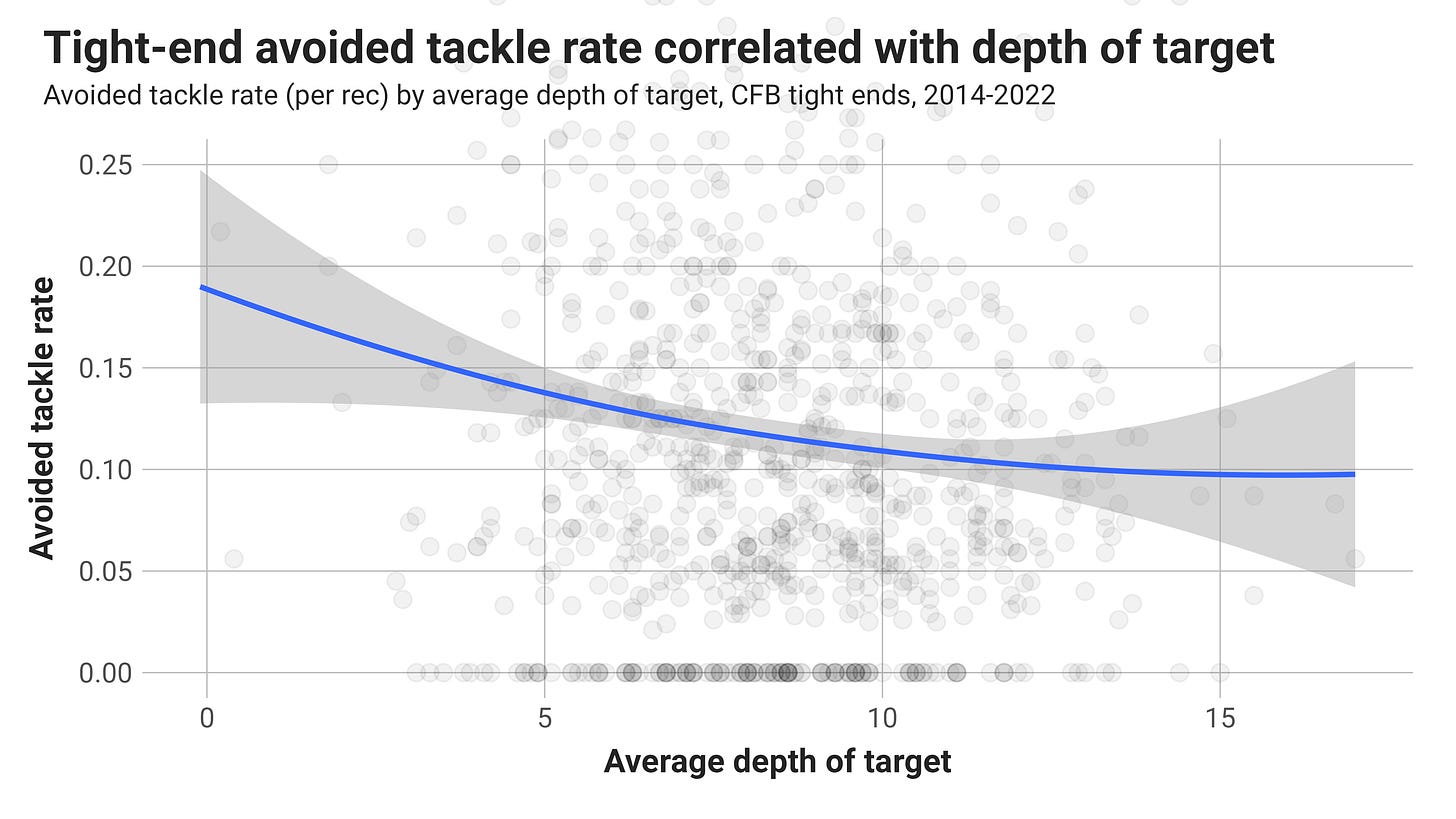

For that reason, I wanted to look at YAC per reception, but also avoided tackles per reception, which might provide more of the signal for NFL success. Being able to operate underneath and and avoid tackles is a highly valuable trait for NFL tight ends, and is probably correlated with maneuvering to find open space in zone coverages. Again looking at the 2023 NFL receiving leaders, George Kittle averaged nearly twice as many avoided tackles per reception as the top-5 wide receivers by total yardage gained.

Looking at the college seasons from 2014-2022, I plotted the drafted tight ends’ avoided tackle rate and YAC per reception in their final college seasons, highlighting those tight end who have gone on to enough success to warrant a decent second contract, or had performed at a high level for at least one year on their current rookie deal.Nearly all of the highlighted group was above the 50th percentile in either avoided tackle rate or YAC per reception, with Hunter Henry near the border of both. The majority of the group resides in the upper-right quadrant, indicating above average performance in both of the admittedly correlated stats.

We’re dealing with a smaller sample here, so not all of the highlighted players are truly elite, as there might only be a handful of truly elite players at the position at any given time. What you can see from the background, unhighlighted data points is that a number of drafted tight ends made it into the NFL without displaying the trait to generate value after the catch, and nearly all of them failed to have a meaningful career so far, or even a meaningful season.

These percentiles have been adjusted to account for depth of target, recognizing the difficulty of generating enough separation to avoid tackles and accumulate YAC on longer targets.

YOU CAN’T TEACH SPEED

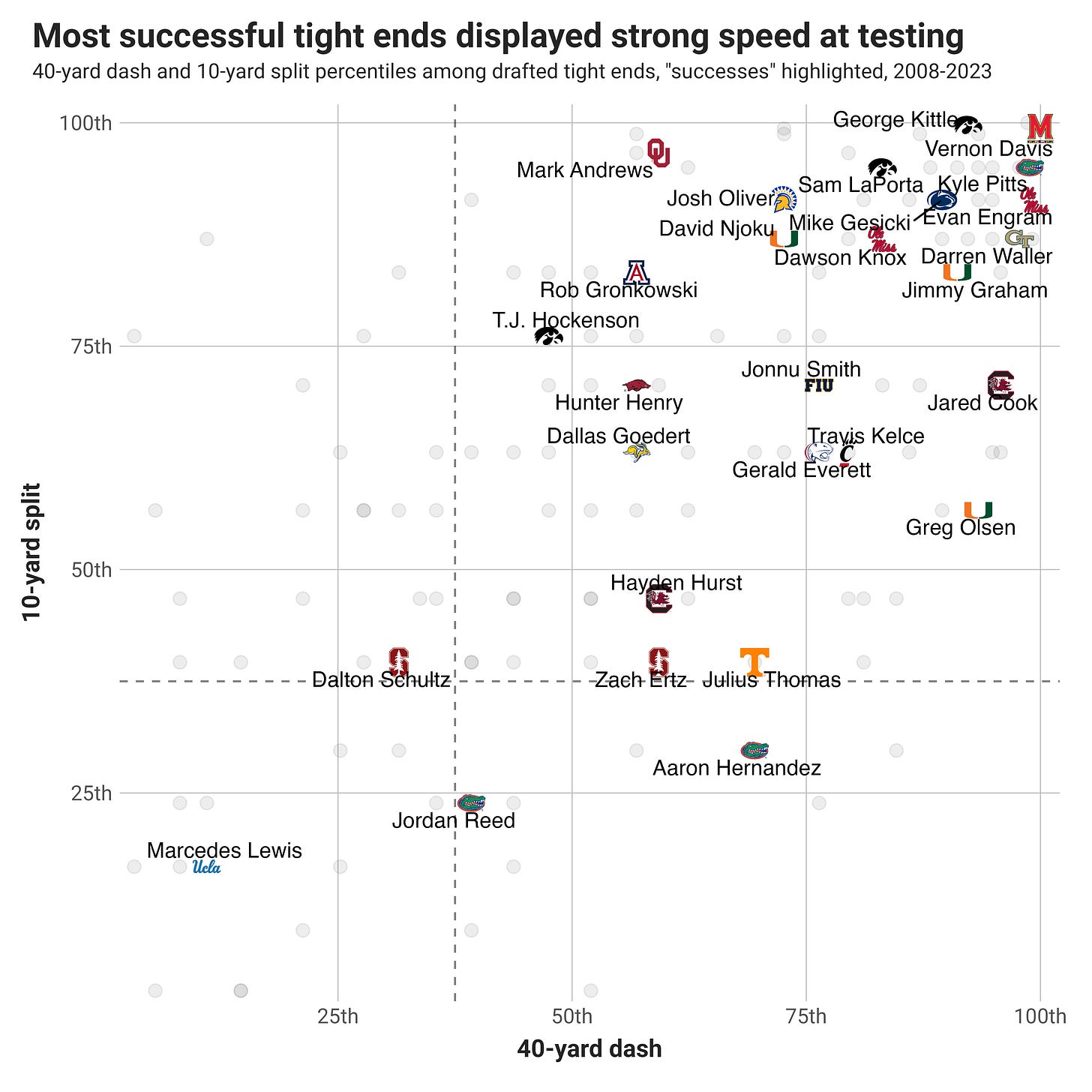

The other trait that I found was best to pair with after-the-catch prowess for predicting tight end prospect success is plain ole’ speed. Specifically, I looked at the percentiles for the 40-yard dash and the 10-yard split, and speed does correlate generally with NFL success at the position. Because this is a combine (or pro day) metric, I have a longer history of data to look at than for PFF college charting, in the plot below going back to 2008, highlighting the same group of tight ends as above, and adding older success like Travis Kelce, Rob Gronkowski, Jimmy Graham, Vernon Davis, Zach Ertz and Greg Olsen.

Most of the successful tight ends are in the top-right quadrant for above average times in the 40-yard dash and 10-yard split, with some of the splits estimated based on forty times.

Marcedes Lewis is the only historical example of a successful tight end during this period that didn’t hit the 50th percentile in either the forty or ten, but there are some mitigating factors. First, he ran these back in 2006 (times have gotten faster, and concurrent percentiles put him around 50th) and was also a bigger move tight end at 261 pounds.

Again, it might seem like a waste of time to point out that tight ends who are fast are the best draft targets, but you’ll see a ton of gray plot points indicating drafted tight ends who weren’t successful in the NFL after posting poor speed times. In fact, 22 of 79 top-100 picks (27%) in my database didn't hit both 50th percentile speed thresholds. NFL teams are still spending valuable picks on players who don’t show strong NFL speed because of something they’re seeing on tape or in prospect blocking, which fills a role but will never be the driver of an elite outcome.

We can’t be certain of whether these faster, successful tight ends would have scored well in the charted after-catch stats in college, but many were in the pros. And looking back at scouting reports for players like Jimmy Graham gives me additional confidence that it was the case that the successes translated speed to avoided tackles and YAC.

Is very light on his feet and moves around quickly for a player so large …. Has the functional playing strength to reach his arms out and avoid tacklers.

I’d be remiss to not include the fact that a major outlier in the tested speed = success equation was Hall-of-Famer and possible greatest tight end ever Tony Gonzalez (FWIW, I’m still #TeamGronk for GOAT). Even considering the context that Gonzalez ran way back in 1997, posting a 4.83-second forty at 244 pounds has to be a below average outcome. I’m not sure about the accuracy of his posted 10-split at 1.68 seconds, but if correct it’s also very slow. Failing to draft Gonzalez due to his poor speed would have been a massive mistake, but you always have to weigh the forward predictive power of outliers, which I generally minimize, with caution.

ASSESSING ALL THE RECENTLY DRAFTED TIGHT ENDS

To simplify the analysis and adhere to the principle of parsimony in analysis, I’m going to look at only tackles avoided and 10-yard split percentiles as individually the more highly correlated to NFL success of the pairings above. In the tables below, I list all the drafted tight ends up to pick 150, or near the end of the fifth round. Each player has listed his draft year, draft position, how many of the 50th percentiles he hit (either 0, 1 or 2), and the percentiles for avoided tackle rate and 10-yard split. I also averaged the two percentiles for an “aggregate” score at the end to compare the historical prospects.

For players missing sprint times, I’m labeling the column “NA” and not giving them credit for a threshold hit. You can decide for yourself from what you’ve seen from the player if those with missing times looked fast enough in college to assume they would have been above the 50th percentile in the 10-yard split.

The overarching lesson for me from these numbers are:

The success rate among tight ends that hit both trait threshold is vastly higher than those that don’t

While there are significant false positives among those who hit the threshold (i.e. aren’t successes), there are almost no false negatives for those who don’t hit both thresholds

Historically, hitting the thresholds doesn’t guarantee success, but missing them almost guarantees failure. Draft picks are dart throws generally, but you can restrict yourself to playing on a board with much better outcomes.

Let’s start with the tight ends taken in the first round since 2015.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Unexpected Points to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.