Super Bowl LVIII, Chiefs-49ers: Advanced Review

The Chiefs prevail in overtime in a virtually even game. Let's dissect the performances, dispel misconceptions about the new OT rules, and criticize coaching decisions

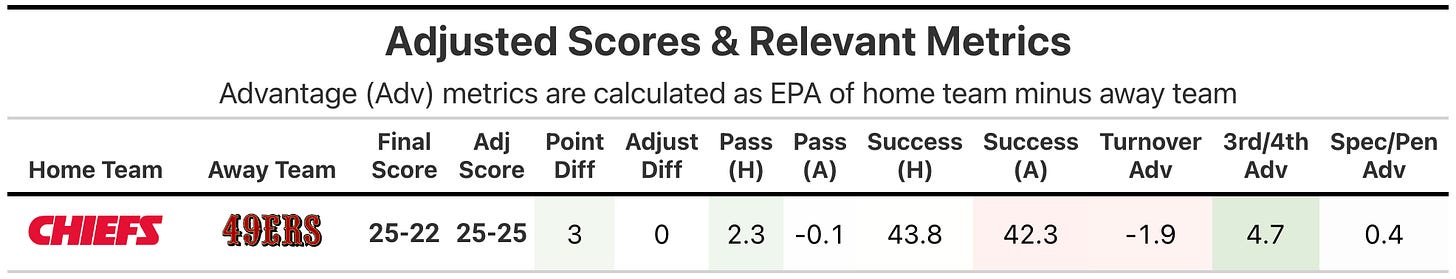

The adjusted scores quantify team play quality, with emphasis on stable metrics (success rate) and downplaying higher variance events (turnovers, special team, penalties, fumble luck, etc). Adjusted expected points added (EPA), in conjunction with opportunity-based metrics like total plays and drives, projects adjusted points. Adjusted scores have been tested against actual scores and offer slightly better predictive ability, though their primary benefit is explanatory.

All 2023 & 2022 and historical Adjusted Scores and other site metrics are available in a downloadable format to paid subscribers via Google Sheet.

Find previous advanced reviews here

** Adjusted Scores table:

“Pass” - Pass rate over expectation (based on context of each play and historical averages

“Success” - Success rate on offense, a key metric in adjusted score vs actual

“H & A” - Home or away team

KC-SF

It took all four quarters and the entire 10-minute overtime to decide the winner, and the adjusted scores agree that the Super Bowl was basically a coin-flip in team fundamentals. Going into this analysis, I assumed it wouldn’t favor the Chiefs with the adjusted scores, as they recovered six-of-seven fumbles (counting the 49ers muffed punt and Chiefs low shotgun snap), yet I didn’t appreciate how much the 49ers benefited from penalties (+3.5 EPA), which I discount in the numbers.

The Chiefs had a material third-down conversion advantage (+4.7 EPA), but it was more about the 49ers struggles on third down (3-of-12, -4.6 EPA) than the Chiefs success (9-of-19, +0.1 EPA). The expected conversion rate for the 49ers was low (34.3%) because of the longer distance they consistently fell into, with seven-of-12 attempts needing nine yards or more. The Chiefs fell into similar third-and-very-long situations on only four of 19 tries.

The Chiefs had a slightly higher success rate offensively, with both teams ending the game with roughly flat expected points. The teams’ mixes of pass-run efficiencies were also highly similar, with two huge rushing fumbles tanking efficiencies in that phase of the game. I often harp on just how damaging rushing fumbles can be, and we saw it in this game. Outside of the muffed punt recovery by the Chiefs, both fumbles were the next highest impact plays of the game in EPA. Expected points value added is derived by taking the post-play expected points versus pre-play, and rushing fumbles often come off plays with high pre-play EP, making the downside of the turnover even greater. In this game, the two fumbles came on first downs.

It was a relatively clean game outside of the three turnovers, yet there also weren’t a ton of big plays offensively. The 52-yard completion from Patrick Mahomes to Mecole Hardman was negated by a subsequent fumble on the drive, accounting for one of the three times the Chiefs’ offense stalled out inside of the 49ers 10 yard-line, totaling only six points on those trips when the peak expected points during those drives combined to 15.2.

The Achilles heel for the 49ers offensive was being unable to convert their strong 46.7% rushing success rate into points. The 49ers lost 5.4 expected points on the McCaffrey fumble, and also at least 1.5 expected points on three non-turnover rushes: a 4-yard loss on 2nd & 10 (-1.8), a one-yard loss on 3rd & 2 (-1.8) and getting stuffed on 2nd & 2 (-1.5). None of their positive designed runs added more than 1.0 expected points. A single explosive run or one less big negative on the ground could have swung the game in their favor.

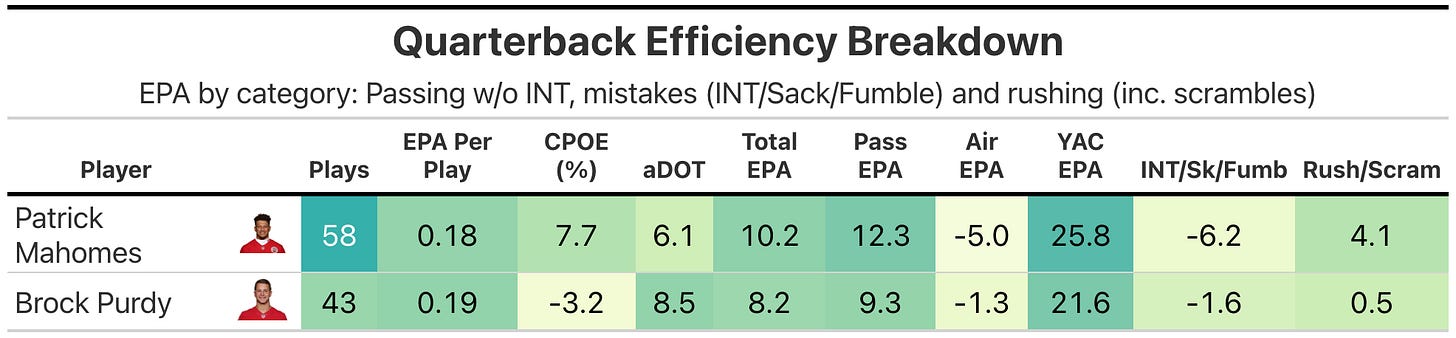

Mahomes and Brock Purdy both had solid-but-not-great numbers by EPA per play, with the former driving results, once again, on the ground. Over 40% of Mahomes’ total EPA came on scrambles and designed runs, including a crucial fourth down conversion in overtime.

That rushing proficiency helped mitigate a rare game of significant negatives for Mahomes, throwing an interception and taking three sacks. Even Mahomes’ interception, in a way, was an example of his keen understanding of situational risk, coming on third & 12, meaning the resulting expected points loss was relatively small at -2.0, not even making the top-15 most impactful plays.

Outside of the 52-yard completion to Hardman, Mahomes was forced to dink-and-dunk down the field, but he did so in a highly effective manner, completing 74% of his passes (+7.7% over expectation).

I don’t think Purdy had a great game, but he played well enough to get the win in a lot of scenarios where the 49ers can get more value out of their running game. Purdy didn’t throw the ball particularly well, but almost totally avoided negatives (zero turnovers, one sack for four yards). There was somewhat a lack of explosion in the passing attack, with only two passes completed by Purdy for more than 20 yards, after averaging 4.2 per game previously this season.

GAME MANAGEMENT TALK

OVERTIME RULES

Let’s get to the various discourses coming out of the game. First, I’ll start with the decision to kick or receive in overtime. Once again, we have a lot of confident opinions that the 49ers did the wrong thing by choosing to receive, almost entirely from people who started putting thought into the decision last night, even though the new playoff overtime rule was passed two years ago. At the time that the new rules were approved, there were good analyses done on the benefits of kicking versus receiving, and none showed a material advantage either way.

We shouldn’t be surprised that the new overtime rules were carefully crafted to minimize any advantage, as they were endorsed and influenced by the NFL’s head of data and analytics, Michael Lopez. He’s one of the best in the business, and explains here why giving a guaranteed second possession works, with advantages for both sides mitigating each other. The kicking team has an second-mover advantage (knowing the results of the first drive), while the receiving team has the extra-possession advantage (being able to get an extra first possession and end the game if it the score is tied after each team had a possession):

What does a guaranteed second possession do?

It secures a benefit – known as the second mover advantage – for the team that starts overtime by kicking off. Teams kicking off to start overtime will always know what is needed to either extend overtime or win the game when they get the ball back.

While the second mover advantage swings the coin toss benefit closer to 50-50, one key advantage remains for the team that receives the ball first. If the opening two drives of overtime end tied, the team that received the ball first gets the ball again in a sudden-death setting. For example, from 2017-21, the team receiving the ball first in overtime averaged 1.6 possessions per overtime session, compared to 1.1 for the team kicking off. As a result, teams receiving the ball to begin overtime won more games after their first possession than on their opening possession.

In a format where both teams have at least one possession, we expect the benefit of winning the coin toss to drop by more than half. In some postseason overtime games, teams may even want to kick off, though that decision could be dependent on team strength and weather conditions.

It appears more people have more difficulty weighing the extra-possession advantage, perhaps due to results-bias of what happened last night, leading to a consensus that kicking is better. It is true that theoretically the kicking team has the ability to fully control whether or not the receiving team ever gets another possession.

In the event that the receiving team scores a touchdown, the kicking team should never allow a third possession, i.e. they should either fail on fourth down trying to score a touchdown, fail on the 2-point try or convert the 2-pointer and win the game. The kicking team never wants to simply match the receiving team’s touchdown and extra point and give the ball back. Taking the roughly 50-50 shot on the 2-point conversion is always preferable to giving the other team a chance to end the game without the ability to respond.

However, people are dismissing the very real chance that overtime does go to a third possession, or the threat of the third possession causes the kicking team to be so aggressive on fourth down that they have to attempt sub-50% conversions. As much as you know the kicking team could go for it on fourth down, would they choose to on fourth-and-long in situations where their opponent didn’t score on the first drive, or in field-goal range after their opponent kicked a field goal?

The fourth-down calculus changes and extends the distances from which isn’t reasonable to go, but attempting to convert something like a 4th & 8 on your own 30 yard-line after your opponent failed to score isn’t a must-go situation. If your expected conversion rate is something like 30% and you know a failure loses the game, you might be willing to punt and take the risk that you never see the ball again. Or if the kicking team decides to go for it in a lower-conversion context to avoid the receiving team getting the extra possession, that’s pressure versus simply punting is another advantage of receiving.

TLDR: don’t believe any confident takes about kicking being the clearly better call and Kyle Shanahan making a mistake by choosing to receive.

FOURTH DOWN DECISIONS - REID GOT LUCKY

A couple places you could make a strong case for coaching poor decisions are with Andy Reid’s regulation fourth-down decisions and some critical third-and-medium calls from Shanahan. According to nflfastR’s fourth-down model, the Chiefs had four different opportunities to go-for-it on fourth downs in regular and gain more than 1% in decision win probability, but chose to kick/punt in every one.

All of these calls would have been of the non-traditional variety to go-for-it, but the value of modeling these decisions is to help us figure out when we should be going for it despite tradition. They fell into two different categories: short distance to go on the Chiefs side of the field and medium distance to go in field goal range:

4th & 1 from the KC 11 in third quarter down 7 points: +3.4% win probability

4th & 6 from the SF 39 in third quarter down 7 points: +2.6% win probability

4th & 2 from the KC 35 in third quarter down 4 points: +2.4% win probability

4th & 6 from the SF 10 in second quarter down 10 points: +1.6% win probability

You can’t blindly accept the model’s output on 4th & 1 due to the importance of true-distance context, meaning is it 4th & inches or 4th & 1-and-a-half. The first listed decision from the KC 11 with the biggest modeled win probability gain was fairly short, about half-a-yard to go after the Chiefs failed to pick up a full yard on 3rd & 1, but did move forward a little. I think it’s safe to assume the model is right that it was a go-for situation.

The second “poor call” by the numbers I also think the model was correct. The result was a made 57-yard field goal from Harrison Butker, but we have to think about this decision without knowing the results. There were pre-game reports Butker was bombing field goals from 70 yards pre-game, but it became more difficult in-game, and the specifics of this kick illustrate how fortunate the Chiefs were to get three points from the decisions. A bad snap was saved, then the kick was a complete line-drive, easily low enough to be blocked yet passing between (not over) the arms of the defenders leaping to make the block. It wasn’t like the model assumed a low probability of making the kick either at 53%. The tipping point for kicking the field goal comes somewhere between 65-70% assumed percentage to make, a number that I’m confident is too high.

The third call was a full two yards to go, and the results of the play mean that the Chiefs benefited greatly from potentially poor decisions. The subsequent punt turned into a muffed return and gave the Chiefs 5.9 expected points and much better field position than a 4th down conversion would have. Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than right.

The last decision is the only one I think could have really gone either way. You don’t want to overplay the fact that the Chiefs get the ball to start the second half, but it is a big factor. You also know that Shanahan was going to be ultra conservative and not try to get any points at the end of the half, lowering some of the downside of giving the ball back with 20 seconds left.

CLOCK MANAGEMENT & CRITICAL PLAY CALLS - SHANAHAN GOT IT WRONG

Shanahan blew the clock management at the end of the first half. I would have started calling timeouts as early as roughly 1:30 left when the Chiefs converted and got to the 25 yard-line. You put pressure on the Chiefs to waste time and potentially call low-upside plays, or if the Chiefs score quickly you have a chance to answer before giving the ball back to the Chiefs to start the second half. Instead, the 49ers used their first timeout with 20 seconds remaining, and took two of them into halftime when they could have benefited from having a real drive to end the half.

Two other calls by Shanahan caught my attention in an aspect of the game I try not to be overconfident in: third-down playcalling. Obviously there’s a big bias to critique play calls that don’t work as dumb and the same that do as genius, but my pushback isn’t the exact call as much as missing an opportunity to play the advantages of knowing you can go on fourth downs.

Specifically I’m talking about two opportunities when the advantage of unexpectedly running the ball on third-and-medium, potentially converting or setting up a shorter fourth-down try:

3rd & 5 at the KC 35 with 2:00 remaining

3rd & 4 at the KC 9 in overtime

The simplification of “analytics” by skeptics is that we never want teams to run the ball. The true bias of analytics is not towards passing or running, but doing what’s most valuable. Most often, that’s passing, but specifically third-and-medium has been shown to be a slight advantage of running. Yet, teams rarely call runs in those situations. On 1,213 third downs with four or five yards to go this season, teams ran the ball only 177 times, or 14.5% of the time.

At worst, I’d say it’s a coin-flip decision, yet teams are passing over 85% of the time. You add the fact that the 49ers have one of the best running offenses in the NFL, and I think the case is even more compelling. The Chiefs blitzed on the regulation 3rd & 5, which was designed to stop a quick passing conversion over the middle, and worked to perfection.

On the second in overtime at the Chiefs 9 yard-line, the 49ers came out in empty, and the Chiefs defensive linemen were in full-on pass rush alignment. Defensive tackles Chris Jones and Tershawn Wharton were beyond 3-tech to 4i-tech, lined up across from the offensive tackles’ inside shoulders.

The 49ers were a little unlucky with a miscommunication that gave Jones a free path to quarterback (Brandon Aiyuk was open for a TD when his defender fell down), but the bigger point is that the Chiefs’ alignment showed that they were fully committed to stopping the pass and rushing the quarterback, driven by the fact that teams rarely run in these situations, even when the EPA value says they should.

In both situations, the 49ers could have unexpectedly run the ball and set up easy go-for-it fourth down decisions, effectively ending the game in regulation with a conversion, or scoring a touchdown in overtime, knowing that a field goal wasn’t likely enough against Mahomes and the Chiefs offense. Whenever teams have third downs that are in the close-but-not-close-enough range for going on the same distance on fourth downs, running the ball should be very much in play, if not the dominant option. I’m sure Shanahan had great passing play calls on those plays, but the most important factor was giving up the chance to run the ball.

Interesting point you bring up at the end on running on third down. I hadn't seen the numbers, but have always thought it was strange that third and short-medium are so often treated as clear passing downs. I suppose we don't know what they would have done given a variety of outcomes of 0-4 yards, it is possible they would kick on anything but 4th and 1 even if that's not the right decision. So given that line of thinking teams probably think of that situation as first down or nothing.

It's also important to point out that on both those drives they had a strong play on first down, and got 0 yards on second (PA pass to the flat and then a run). Those plays seemed to be the "right" call, but then on third down it retreats to a more predictable call. So SF went from very favorable situations in a high leverage moment to being "forced" to throw.

Do you have the numbers on how successful the run games were without the fumbles? I have seen a few places that are saying SF should have run more. Maybe that's the case, but KC was seemingly setting up to stop the run on early downs. CMC also 30 touches (22 rush and 8 pass). So not sure if they are advocating for Elijah Mitchell to get more carries. Seemed to me the bigger issue was not being able to get Aiyuk, Samuel, and especially Kittle involved significantly until late in the game.

You need to rewrite the final two paragraphs. Really ruins the whole piece.