Instant draft grades are mostly bad, but waiting years for results is even worse

Grading the NFL draft should always be done based on what we know in the moment, but most evaluators have a bad understanding of what really matters

The upcoming post-draft week will be a time for the draft-evaluation industrial complex to give their verdicts on the winners and losers of the NFL draft. There will be a vocal pushback from results-based thinkers, and fans of teams with general poor grades, to the idea that you can reasonably assess the draft without having any idea of how the prospects selected will actually play in the NFL.

While I’m a strong advocate of process-based thinking and assessment, I have to admit #teamresults has a point. It’s not that their method of waiting years after the draft to have an opinion makes any sense - it doesn’t. It’s that nearly all of the draft grades you will see this week will do a poor job emphasizing the decisions that have real predictive power. Most draft grades will focus on the individual player selections, and whether their rank ordering aligns with the pre-draft opinions of the analyst. If media draft experts build their credibility on the hammer of player evaluation, then draft assessment becomes the nail of agreeing or disagreeing with the valuation of the players selected.

If most pre-draft prospect evaluations are wrong and overconfident going into the event, they’re even more wrong and overconfident coming out of it. We know that NFL teams are privy to loads of information and data we don’t have in the public (medicals, interviews, references, tracking data, cognitive testing), and each team has a robust group of evaluators and analytical specialists whose entire jobs are filtering and weighting the information for their final assessments. What’s revealed to the public during the draft should have a much greater impact on how we view prospects than how right or wrong NFL teams were in how they viewed them.

It’s difficult for most people to understand that what’s ultimately the most impactful aspect of a decision (the specific prospect chosen) isn’t the best way to judge the decision. If you’re playing the lottery, the most impactful decision will be the number you choose, but we don’t give someone credit for great number-picking if they win. While the draft isn’t as inherently random at the lottery, the degree to which there can be relative advantage in prospect evaluation is mostly whittled away by 32 teams of experts who are all very good at their jobs.

Two offseasons ago, PFF’s Timo Riske looked at the team draft results over a from 2017-2020, and found that have been material differences in draft results during that period, which feeds into the idea that some front offices are better at drafting. But when Riske looked back further at the best (Bucs, Saints, Colts, Steelers) and worst teams (Broncos, Pats) in his recent sample, he found no long-term correlation.

The analysis we performed is purely descriptive — it explains what happened. The next questions pose themselves naturally: Does this mean Jason Licht and his scouts are superior talent evaluators? What about Chris Ballard or Mickey Loomis?

The answer to these questions is probably no.

For example, if we recreated the last chart for 2014-16, Licht’s first three drafts as GM, the Buccaneers rank 29th of 32 teams. Meanwhile, Chris Ballard was evaluating draft prospects for the Chiefs from 2013 through 2016, and they ranked 23rd during these four drafts. Kevin Colbert’s Steelers rank sixth in the chart above but only 24th from 2013 through 2016.

On the other side of the spectrum, John Elway's Broncos rank first from 2011 through 2016 — which explains the Super Bowl title in 2015 — but Denver hasn't had much draft success in recent years. The same is true for Bill Belichick and the Patriots, who ranked second from 2011 through 2016 but have missed on a few prospects in recent years, explaining their roster's recent decay.

It isn’t that prospect evaluation doesn’t matter, it’s that all NFL teams pour so many resources and expertise into the task that relative success and failure will be narrow, especially over a longer timeline. You shouldn’t take away from the data that no teams are really good at prospect evaluations, instead it’s that all teams are really good, and likely much better than outside evaluators.

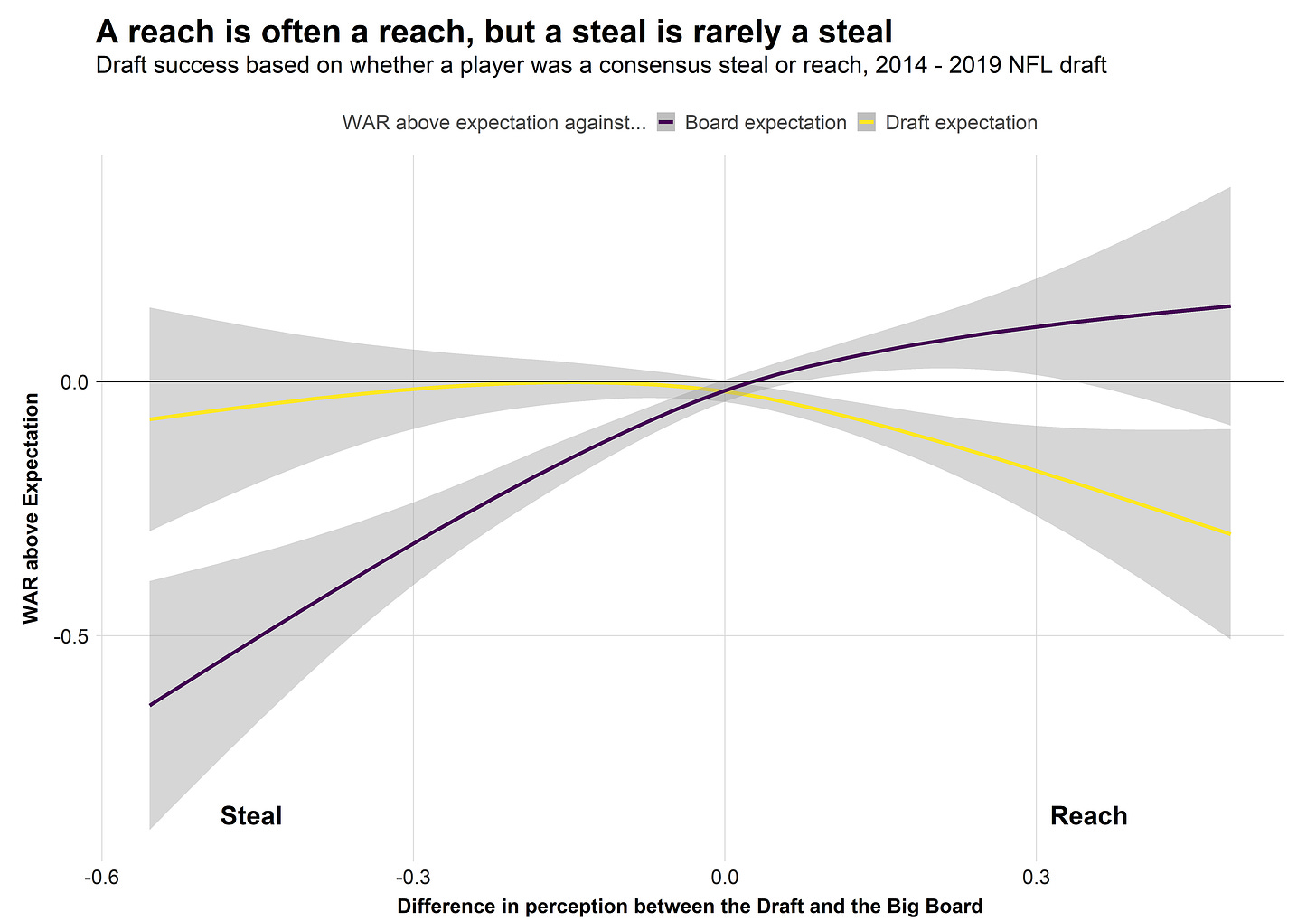

There is some evidence that teams do error when they stray too far from public consensus, but only on one side of the equation. PFF’s Riske analyzed “steals” and “reaches” in the NFL draft, quantified as the difference in draft value according to where a prospect was taken in the draft and his consensus big board ranking.

Players who were drafted later than their consensus big board rankings (“steals”, left side of the plot) didn’t outperform their draft-position expectation (yellow curve), but those who were taken earlier (“reaches”, right side) did materially underperform. In other words, we should be more confident that a team reaching on a player versus consensus opinion is losing value, than a team drafting a player far later than consensus ranking is gaining.

Beyond the empirical evidence, there’s logic to back the idea that steals aren’t a thing but reaches could be. In order to lose value reaching on a player, only one team has to have a bad assessment. The decision to reach and draft the player is entirely within one team’s control. For steals, it’s a combination of multiple team opinions. If you draft a player 15 spots lower than his consensus ranking, that means 14 other teams disagreed with the consensus ranking and allowed that player to fall. 14 independent groups of decision-makers had to all be wrong. Logically, it’s more likely for one team to be incorrect and create a reach than several wrong to create a steal.

Another reason why steals are less likely than reaches is the nature of most non-public prospect information. It has a strong bias towards adding negativity on a small number of prospects. Whether it’s worrying medicals, or poor character evaluations from interviews and references, the upside in evaluation is the equivalent of checking a necessary box, while the downside is massive. Steals are more likely to have a negative assessment in an area of non-public information, revealing weaknesses in the public evaluation.

WHAT WE CAN BE CONFIDENT MATTERS IN THE DRAFT

I won’t be able to resist the NFL draft grading game and will release my grades early next week. Knowing that specific player evaluation is the wrong way to do draft evaluation, at least when it comes to steals, what are the right ways to judge how teams added/lost value during the draft? I’ll list them below in order of confidence and impact. When I write up the draft grades, I’ll also translate everything into a comparable metric (value in dollars) so that we can combine different aspects and net out the good and bad moves.

TRADE VALUE GAINED/LOST

This is the aspect of the draft that has the most impact and it’s something we can be very confident will, on average, benefit or harm teams. The right move, generally, is to trade down and accumulate more draft capital to spread out among many players.

It’s a reasonable question to ask why teams aren’t as good as making fair trades as they are in relative player evaluation. The simple answer is that all the time and effort teams put into evaluation dwarfs what they spend analyzing trade value, and every trade up in the draft can be viewed as a type of reach.

If you’re willing to pay more in draft capital than any other team for the right to draft players at a particular draft slot, that means no other team, including the one trading out of the spot, is motivated enough by their value assessment to outbid you. The team trading up likely has a misaligned view on the prospect they end up taking, and are willing to give up proportionally more draft capital to secure that player. Teams are more likely to be right that prospect X is better than prospect Y than the degree to which prospect X is better than prospect Y. It’s an overconfident assessment of the latter that causes value in trading back in the NFL draft.

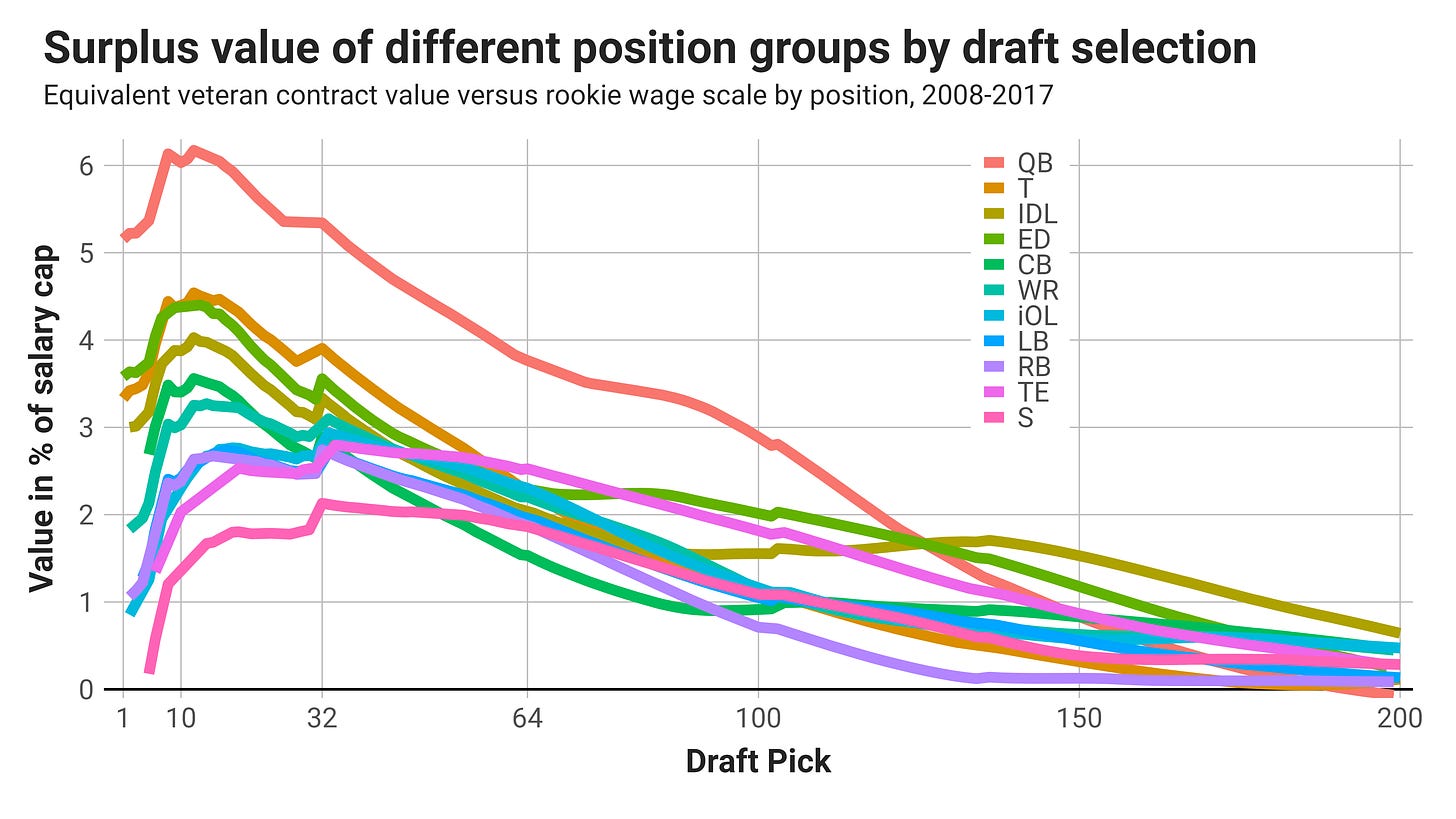

We can measure the value gained and lost on trades by looking that the expectations of surplus value gained (equivalent player value on second contracts minus rookie contract value) for picks in different slots, Surplus value should be the foundation for combining multiple aspects of draft value together and judging decisions.

POSITIONAL VALUE GAINED/LOST

It’s seems a bit silly that NFL teams wouldn’t have a full grasp on which positions add the most value in the NFL draft, but the evidence clearly points in that direction. In fact, building surplus value curves based reveals large differences in the expected value for draft selections based on position. It’s essentially the NFL extension and free agent markets telling the NFL draft market that it’s wrong. My research into the subject gives up a baseline for assuming purely on the position selected if he will provide more surplus value, on average, than all picks at the equivalent draft slot.

Drafting a running back or safety in the first round will, on average, provide less value to teams than taking an offensive tackle or edge rusher. When the latter positions hit, they hit really big, as reflected by the enormous size of this second contracts.

The mismatch in value likely comes from teams being overly concerned about hit rates and filling needs than the range of outcomes for different positions. The traditional “big board” for teams lists every position (minus specialists) together with their draft grades, which focus at the level of player they will become relative to their position. We still see tons of references to where players are on teams’ one-size-fits-all big boards, and even teams themselves after the draft explain their decisions to take a lower-value position early by de-emphasizing the importance of positional value.

It’s also likely that teams don’t fully appreciate and lack of certainty in their rosters going into the draft, and overvalue fitting draft selection to need, making them willing to give up some positional value to fit their unique situation. Outside of having an elite quarterback, there are fewer teams than we think who are truly set at high-value positions like edge rusher, interior pass rusher, cornerback, wide receiver and even offensive tackle. Injuries and player declines fall into the category of unknown but expected outcomes. Teams can’t account for them with certainty in the offseason, but building duplication and the most important positions will, on average, make teams better able produce better than filling less important needs.

REACHES AND STEALS

I will incorporate reaches into my draft grading analysis, but it will be the least influential part of the overall grades. Reaches can be quantified by the loss of surplus value based on draft slot versus consensus, which I’ll then discount to reflect the empirical evidence that shows reaches aren’t as damaging as consensus would expect. Steals will not be part of my analysis, even though it’s fun to give credit to teams that draft players you like.

The importance of reaches and steals reflect the larger team of draft grading analysis: it’s easier to identify mistakes than genius. Not messing up and following the strong logical and empirical evidence might sound easy, but very few teams hit the bar consistently.

Love this article. Results oriented thinking & preconceptions on players dominate the discourse. I know people get tired of the "nerds" talking about positional value but it doesn't make it less right. Curious to see your full opinion on the Lions, Texans, & Falcons. I'm seeing several galaxy brain explanations to justify their drafts.