2024 Adjusted Quarterback Efficiency: Through Week 17

The best measure of quarterback value, adjusting for YAC, drops, turnover luck, SOS, blocking and other factors

This analysis is my best attempt to discount and adjust various elements of quarterback efficiency and get to the number that most accurately reflects fundamental play. There are a number of elements of quarterback efficiency - which also directly affect team performance - that are more dependent on luck (variance) than skill.

I aggregated many of those luck-based elements, with additional factors like passing scheme ability to generate yards-after-catch, in my Adjusted Quarterback Efficiency (AQE) metric.

The measures that I believe are most luck-based and part of this analysis:

Interceptions: FTNData tracks “interception-worthy throws”, which I compare to actual interceptions on a play-by-play basis, and also adjust for expected interception return. Longer INT returns have a dramatic effect on the EPA, whether the quarterback’s fault or not.

Drops: I calculated the expected drop rate for throws, based on location, and compared them to actual drops and determined the EPA lost/gained.

Fumbles: Whether a fumble is recovered by the quarterback’s own team or not can turn a slightly negative play into a massive loss. I look at expectations for recovery based on different types of fumbles, and whether the quarterback himself recovers the fumble or a teammate (luckier).

Yards After Catch: A higher portion of yards after catch should be credited to receivers or scheme than quarterback, at least in comparison to throws where the yards gained were mostly through the air. I adjust down EPA generated on passes with a relatively high proportion of YAC.

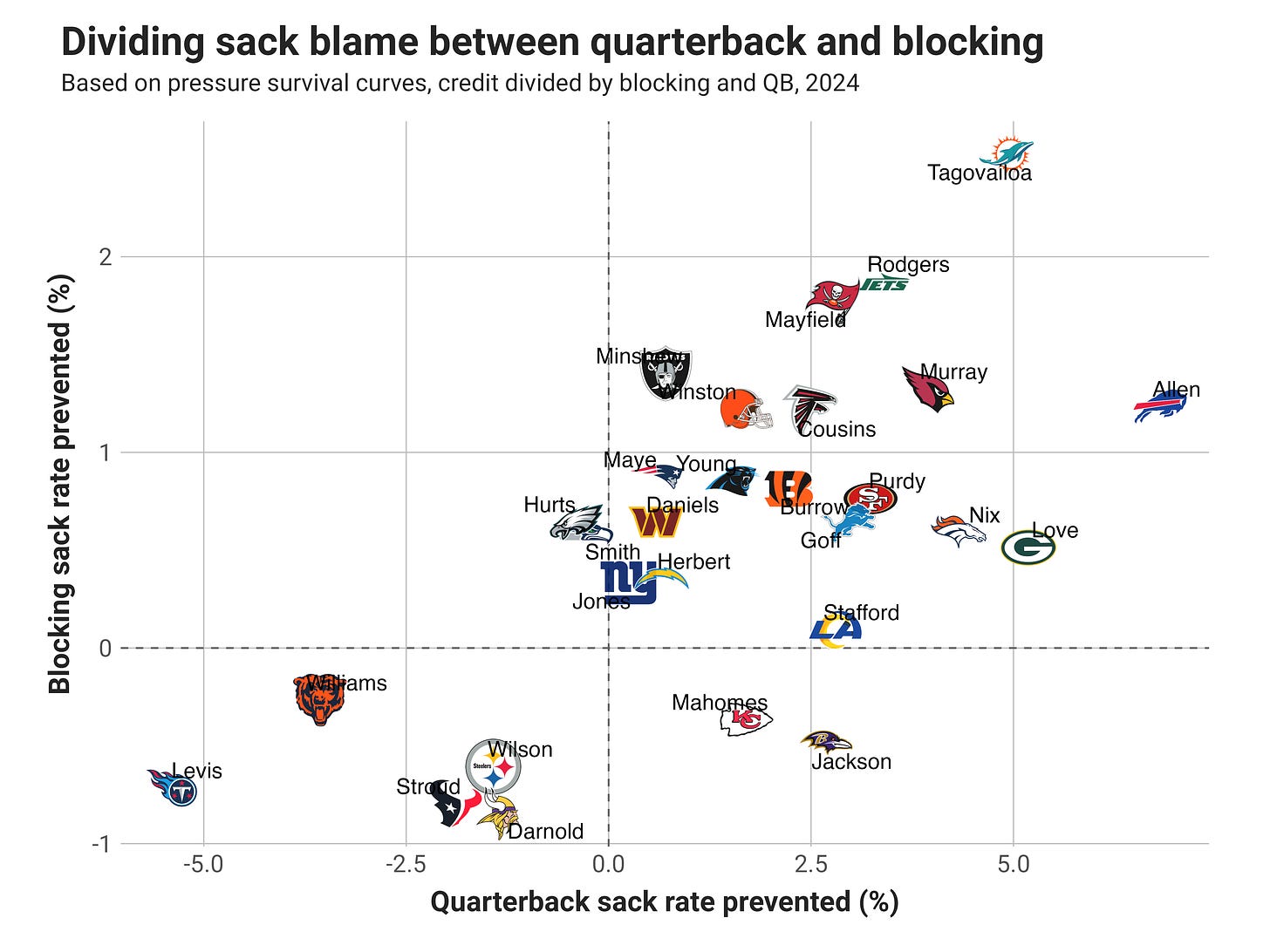

Sacks caused/prevented by blocking: I introduced this element in Week of 2024, using survival curve analysis that accounts for time-to-pressure, time-to-throw and contextual play elements from FTNData’s charting. Through this, I can divide sack credit/blame versus expectation into holding the ball too long (quarterback) and allowing pressure too quickly (offensive line). I back out the portions belonging to blocking.

Defensive Pass Interference: There are so many underthrown balls that turn into big DPI gains that need to be recognized as partially luck. By their very nature, DPIs are not “open” receivers with the coverage defender close enough to affect the receiver.

Strength-of-Schedule: This is the one element that is most difficult to judge this early in the season. With three games played, a great offense can have a bigger effect making the defenses they played look “bad”, and vice versa, than might be the truth. But it still matters.

Weather: Based on expected EPA gains/loss versus average in different elements, based on wind, humidity and temperature.

If you want more details on many of the calculations, check out the Adjusted Quarterback Efficiency (AQE) primers from last season.

Archive of past AQE posts, including my analysis of who deserved the 2023 MVP leveraging this metric

YTD 2024 ADJUSTED EFFICIENCY RESULTS

First, here’s the chart for sack adjustments, with particular note that my model estimates holding onto the ball too long (i.e quarterback) is responsible for most of sack rate over expected, and time-to-pressure (i.e. blocking) a lower amount. Sacks are a (mostly) quarterback stat.

The next plot below shows each quarterback who has been involved in 250 plays this season (dropbacks plus designed runs). There are two points for each quarterback: 1) The team-colored dot for the actual EPA per play the quarterback has this season and 2) The quarterback headshot representing the adjusted quarterback efficiency (EPA/play). There is also a team-colored line linking the two on each row.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Unexpected Points to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.